By Rabbi Moshe Goodman, Kollel Ohr Shlomo, Hebron

בס”ד

לשכנו תדרשו

Discover the Holy Presence in Our Holy Land

Israel’s Encampment In The Wilderness

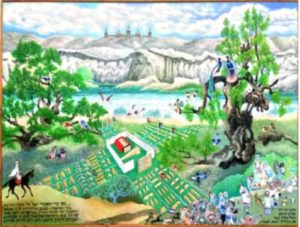

In this painting, we see the Mishkan and Israel’s encampments surrounding it in the Wilderness – central themes of parshat Bamidbar at the center. Although Nachshon did tie this painting to parshat Bamidbar, it is clear that this painting could also be tied to parshat Dvarim, as the verses written at the bottom right and left sides of the painting are to be found that parsha. These verses tell about the expected crossing of the Jordan to the Holy Land, and indeed we see Israel’s encampment in the painting adjacent to the Jordan River, while the Holy Land is depicted in whitish colors, as white is associated with the Holy, as we noted in parshat Teruma and other places (see the Arizal’s code of white dress for the Holy Shabbat). Also, note the fortified city at the top-center of the painting in a straight line above the Mishkan. This quite clearly alludes to Jerusalem, a fortified city at the time of Israel’s crossing the Jordan. It seems that Jerusalem is directly above the Mishkan to signify that the Temple in Jerusalem is indeed a continuation of the Mishkan. Also, the verse at the left hints at the Temple in the word “vehaLebanon,” which our Sages homiletically interpret to refer to the Temple which “malbin” – “whitens,” i.e., causes atonement, for the sins of Israel (here again the white-holy theme).

Moshe Rabeinu and Aharon HaKohen are seen to the right, teaching the various types of people of Israel, and indeed the verse next to them says that Moshe taught Israel at the Eastern Bank of the Jordan. On the left, we see a white-cloaked figure, which from other paintings of Nachshon seems to hint at the Mashiach, which according to the Zohar, is considered a continuation of Moshe Rabeinu, found on the parallel opposite side of the painting. Next to this figure is the verse that also mentions the giving of the Land to the Patriarchs’ offspring, which can also hint at Israel’s return to the Holy Land in the Messianic era.

Indeed, we see three trees in the painting, which may hint at these Patriarchs (also see Rebbe Nachman’s story of the Lost Princess, which describes three giants with three trees). Around these trees, we see ten couples of birds, which seem to remarkably correspond to the ten sefirot. Three couples of birds are seen facing each other, three couples of birds, the male, and female, are seen separated from each other, and four couples are seen face-to-back. Kabbalistically speaking, couples facing each other represents the attribute of kindness, couples separated represents the attribute of judgment, and a face-back relationship can be described as a middle path between the two previous extremes. Indeed, according to the Kabbalah, there are three sefirot that belong to the “right side” of kindness, three sefirot that belong o the left side of judgment, and four sefirot that belong to the “middle path.” Our Sages say that Israel is compared to a bird (for this reason, the bird in Brit bein Habtarim was not split). Although there are other metaphors for Israel, the image of a bird in this painting may also hint at the unique movement of ascent and flying of a bird, which may hint at Israel’s movement and ascent towards the Holy Land and Temple central themes in this painting.

Of course, Hebron carries a central place in Israel’s ascent to the Holy Land, as it is through this city that Kaleb passed and received inspiration to bravely speak in favor of moving to the Holy Land and conquering it for the Holy People Israel.