An American traveler gets warm hospitality from Jews in Hebron, a chilly reception from others.

Excerpts from The handwriting of God in Egypt, Sinai, and the Holy Land : the records of a journey from the great valley of the West to the sacred places of the East

by Reverend D. A. Randall

Published: JOHN E. POTTER & CO., 1868.

page 207 – 213

FERTILE GRAPE COUNTRY

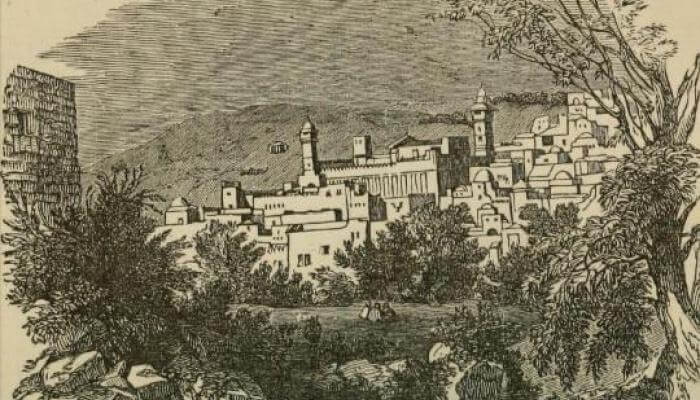

As we approached Hebron, we found the country more fertile, and in a better state of cultivation than any other portion we had yet seen. The valleys were broader, the hill-sides more sloping, and sometimes covered with brush-wood. Upon many of the steeper acclivities the old terraces were still kept up, and vineyards, and the olive and the fig yet flourished…

ABRAHAM’S OAK

…But here, too, is the Plain of Mamre, and there is Abraham’s oak, spreading wide its luxuriant shade… “But you do not believe,” says one, “this is the oak under which Abraham pitched his tent?” No; though some of the credulous Arabs about you will affirm it is the veritable one. But though not the one, it is a descendant, and a conspicuous one among the very few representatives of its ancient progenitor. There it stands, and there it has stood probably for a thousand years. This tree stands alone, the ground about it smooth and covered with a thick carpet of grass. It is twenty-three feet in circumference at the base, and its huge branches spread over a diameter of about ninety feet. It stands, one of the last of that sacred forest, where Abraham entertained angels as his guests, and communed familiarly with his Maker. A walk of about twenty-five minutes from Abraham’s Oak down the valley brings us to HEBRON.

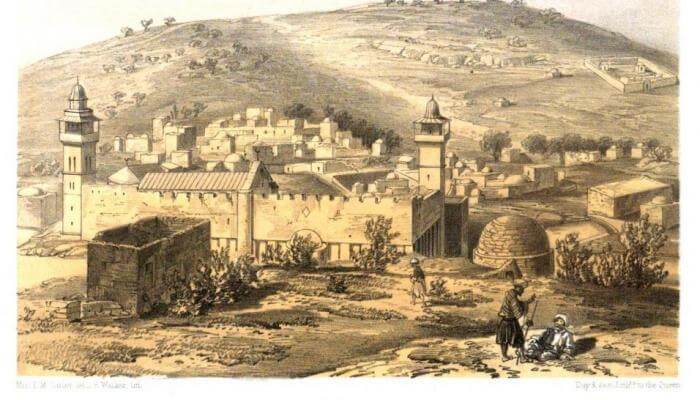

MODERN HEBRON

Modern Hebron contains a population of about ten thousand. The houses are mostly of stone, two to three stories high, and very strongly built. For some half a mile before entering the city, we were traveling upon a road coarsely paved with large boulders, and walled on each side five or six feet high. An archway supporting a gate, seemed to be built merely to defend the road, as there is no wall about the town. A small garrison of Turkish soldiers are quartered here, as well as in all the other prominent towns of Palestine. We entered the place about two o’clock.

JEWISH HOSPITALITY

There is no hotel, or public house, for the accommodation of travelers. We made application to a Jew who had been recommended to us at Jerusalem. One of our number could converse with him in German, and in that language the negotiation was conducted. There were seven of us in company. He had but one room and one bed. It was at last arranged that we should have the room, lunch, supper and breakfast for five dollars. They were a kind-hearted family, and did the best they could for us ; but with the miserable, filthy cookery, the camp on the floor, and the multitude of fleas, we did not pass a delightfully pleasant night.

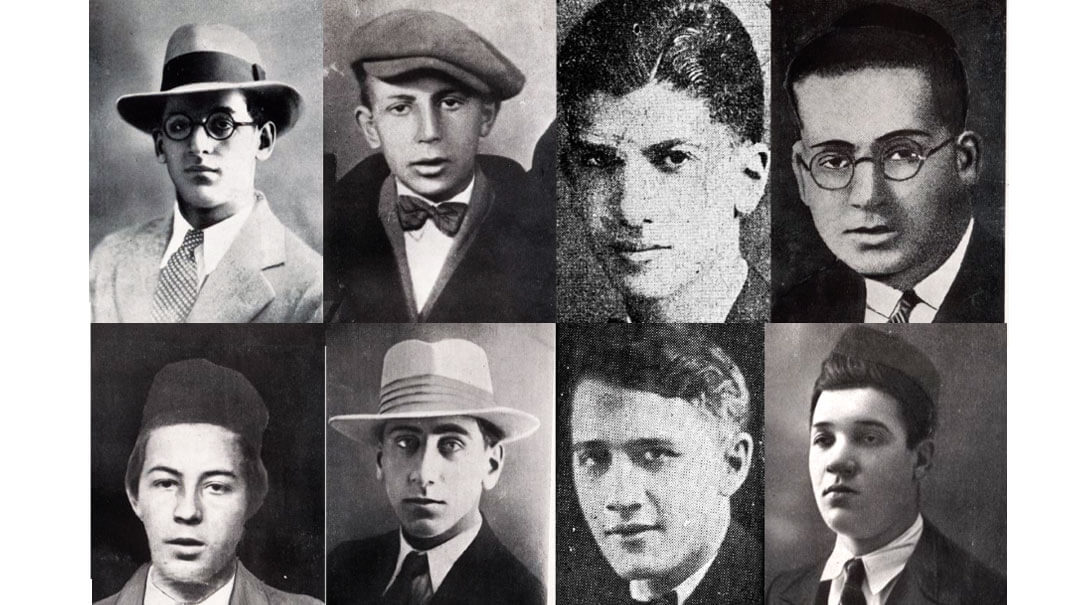

We learned from our host that there were about forty families of Jews in the place. Many of the race make a pilgrimage here to visit the home and burial place of their great ancestor, but Moslem intolerance prevents many of them from making it a home. Aside from a few Jews, Turkish soldiers and native Mohammedans make up the population. Franks and the Frank dress are much more of a novelty here than at Jerusalem and Bethlehem, as but few visit the place.

The people stared at us; the children followed after us; some of the ruder ones hooted at us, and occasionally a stone would come whirling along our path. We walked through the bazars, and bought oranges, figs and raisins, and visited some of the establishments where glass bracelets, beads and other ornaments are made, large quantities of which are manufactured here and exported to other cities.

POOL OF DAVID

Among the curiosities of the place are two large pools, or reservoirs of water, evidently of great antiquity. The lower one is called the Pool of David.

It is a square, each side one hundred and thirty feet, the depth fifty feet. It is very firmly built, with large hewn stones. It affords an abundant supply of water, a large stream constantly flowing through it. This is supposed to be the pool over which David hung the murderers of Ishbosheth, as recorded in the 4th chapter of 2nd Samuel. Tradition also points out some other localities here, but they need evidence to authenticate them, or are too absurd to claim credence, and we did not inquire for them. Such are the tombs of Abner — of Jesse, David’s father — the spot where Abel fell beneath the murderous hand of Cain, and the red earth from which Adam was made. But the great attraction of the place, the sacred spot which Jew, Christian and Moslem alike reverence, is the CAVE OF MACHPELAH.

BANNED FROM THE TOMB OF MACHPELA

This cave is upon the hill-side, close upon the borders of the city. Of the identity of the place there can be little doubt. Through a long succession of near four thousand years it has been preserved ; Jews, Christians, and Moslems have in turn possessed it, and watched over it with jealous care. It is now inclosed by a massive stone wall, two hundred feet long, one hundred and fifty feet broad, and about sixty feet high. Within this harem, as it is called, or forbidden inclosure, stands a Turkish mosque, once a Christian church, and for aught I know, before that a Jewish synagogue. Beneath that mosque is the cave. The story of the little cluster of graves concealed there, is best told in the pathetic language of Jacob. In the land of Egypt he gathered his sons around his dying bed, and exacted an oath from them that he should not be buried among strangers in Egypt. “I am to be gathered unto my people ; bury me with my fathers in the cave that is in the field of Ephron, the Hittite. There they buried Abraham and Sarah his wife ; there they buried Isaac and Rebekah his wife ; and there I buried Leah.”

And Joseph went up from Egypt with a great retinue of chariots and horsemen, and servants, and kindred, with great pomp and ceremony, and laid the embalmed body of his father to rest with his kindred. Here, then, within that massive wall, beneath the dome of that mosque, are enshrined the ashes of the six ancestors of the Hebrew nation. Is it any wonder that the Jew still lingers around this consecrated spot — that they should cling to it as they do to the moss-grown stones that mark the foundation of their Holy Temple?

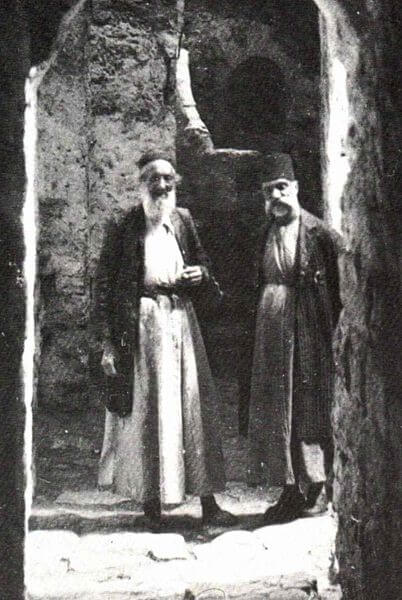

Would you like to visit this sepulchral abode of the venerable dead? You attempt it at your peril. You will not have reached the bottom of the stone steps that ascend to the door of the inclosure, before a dozen Turkish soldiers will stand athwart your path, and a dozen gleaming bayonets will warn you back. Like the tomb of David, on Mount Zion, or the site of Solomon’s Temple, on Mount Moriah, it is too sacred a place to be polluted by the foot of a Christian. For many hundreds of years it has been thus jealously guarded and it has been only by accident or stealth that any knowledge of the interior could be obtained. Why is this? Mohammedans have a high regard for the patriarchs of Old Testament history, especially for Abraham, whom they call El-Khulil — “the friend of God.” In the long succession of wars that have taken place for the possession of these ancient and sacred places, in which Jew, Christian, and Mohammedan have alternately held the mastery, a deep and settled spirit of hostility has been nurtured. For many generations it has been perpetuated, and many more will elapse before it will be eradicated. After many changes, the Mohammedans, in 1187, succeeded in wresting this place from the crusading Christians. They converted the church into a mosque, closed the gates against the admission of Christians, and with most unwavering hostility, have not to this day relaxed in the least their jealous watchfulness over it…

I was aroused from my revery by a troop of young Hebronites, who came noisily upon me, with a lot of old coins, beads and relics, which they were anxious to dispose of for a few piasters. I stopped to barter with them, and they followed me to the foot of the hill and into the town, until I was forced, even with rudeness, to check their importunities.

Our visit to the home of the patriarchs was over. We had fifteen to eighteen miles to walk on our return, and the sun was already shining hot in the heavens. We bade farewell to the Jewish family that had opened their doors for us, left Hebron and all its interesting associations behind, and retraced our steps homeward.

* For full text click here.

(article originally appeared here)